Five Famous Fictional Scars

Out of suffering have emerged the strongest souls;

the most massive characters are seared with scars.

― Kahlil Gibran

In the real world, populated by real people, a scar is typically considered by patients and dermatologists alike to be a clinical problem to be solved, an imperfection to be erased, or an unsightly blemish to be managed. In the world of fiction, by contrast, the appearance of a scar in a story often plays a highly functional role in helping to define a character’s personality and illuminate his or her motivations.

One of the earliest scars in the literary canon is mentioned in the Biblical Book of Genesis, where God is said to have “set a mark upon Cain” for the crime of killing his brother Abel before banishing him to dwell “in the land of Nod, on the east of Eden.”

This “mark,” popularly thought to be a scar placed on Cain’s forehead, is echoed in John Steinbeck’s 1952 novel, East of Eden, where the brooding, violent farmer Charles Trask is marked with a dark scar on his forehead, caused accidentally while moving a boulder from his fields.

An even more well-known forehead scar is sported by the eponymous hero of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series of novels. This distinctive cicatrix, shaped like a lightning bolt, inspires Harry’s bitter rival Draco Malfoy to confer on him the insulting moniker “Scarhead.” But more than just an odd-shaped blemish that throbs when Harry is in danger, this scar is a physical relic of evil Voldemort’s failed attempt to kill him when he was just a baby.

Thus, it is intended as an outward sign of Harry’s inner suffering for losing his parents, who sacrificed themselves to save his life. At the same time, it symbolically marks “The Boy Who Lived” not just as cursed, but also as “the chosen one” who will ultimately defeat the forces of darkness.

Indeed, it is such a potent reminder of his destiny that Professor Dumbledore declines to cure it by magic: “Scars can come in useful. I have one myself above my left knee which is a perfect map of the London Underground.”

One can cite many other examples of such “literary scars.” Here are five more fictional characters with scars of particular note.

Odysseus

So he spoke, and the old dame took the shining cauldron with water wherefrom she was about to wash his feet, and poured in cold water in plenty, and then added thereto the warm. But Odysseus sat him down away from the hearth and straightway turned himself toward the darkness, for he at once had a foreboding at heart that, as she touched him, she might note a scar, and the truth be made manifest. So she drew near and began to wash her lord, and straightway knew the scar of the wound which long ago a boar had dealt him with his white tusk, when Odysseus had gone to Parnassus to visit Autolycus.

— Homer’s Odyssey, Book XIX (translation by A.T. Murray, 1919)

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Sometimes a scar serves as a key narrative device to move the action of the story along. A good example is the wound that Odysseus received while boar hunting as a youth. The mishap foreshadows the hero’s character traits of impulsive daring and mettle, as proven by his actions during the Trojan War. Many years later, at the end of his epic journey home to Ithaca, the resulting scar plays an important role in the dramatic revelation of his identity. No one recognizes him until the woman who raised him—his old wet nurse and servant, Eurycleia—washes the feet of this seeming “stranger.” She immediately knows who he is when she spots the scar on his leg, unmistakably the identical one that the young Odysseus received while boar hunting on Mount Parnassus.

Rosa Dartle

There was a second lady in the dining-room…who attracted my attention: perhaps because I had not expected to see her; perhaps because I found myself sitting opposite to her; perhaps because of something really remarkable in her. She had black hair and eager black eyes, and was thin, and had a scar upon her lip. It was an old scar—I should rather call it seam, for it was not discolored, and had healed years ago—which had once cut through her mouth, downward towards the chin, but was now barely visible across the table, except above and on her upper lip, the shape of which it had altered.

• • •

I could not help glancing at the scar with a painful interest when we went in to tea. It was not long before I observed that it was the most susceptible part of her face, and that, when she turned pale, that mark altered first, and became a dull, lead-colored streak, lengthening out to its full extent, like a mark in invisible ink brought to the fire.

— David Copperfield, Chapter 20

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Charles Dickens was famous for populating his lengthy novels with a plethora of memorable characters, both major and minor. One tool at the disposal of such novelists to help readers tell all these characters apart is to emblazon certain ones with some distinctive physical trait. In the case of Rosa Dartle, it is a livid facial scar that first draws the attention of the narrator (and thus the reader). A bitter, savagely sarcastic spinster, Rosa Dartle is revealed to secretly harbor an unrequited passion for Copperfield’s friend, James Steerforth. Moreover, in the recounting of how she received the scar (from Steerforth himself in one of his violent rages as a child), the reader gains some insight into her psychology, and we can begin to appreciate how her self-conscious pain and thwarted love have curdled into resentment and self-loathing:

“She is very clever, is she not?” I asked.

“Clever! She brings everything to a grindstone,” said Steerforth, “and sharpens it, as she has sharpened her own face and figure these years past. She has worn herself away by constant sharpening. She is all edge.”

“What a remarkable scar that is upon her lip!” I said.

Steerforth’s face fell, and he paused a moment.

“Why, the fact is,” he returned, “I did that.”

“By an unfortunate accident!”

“No. I was a young boy, and she exasperated me, and I threw a hammer at her. A promising young angel I must have been!” I was deeply sorry to have touched on such a painful theme, but that was useless now.

“She has borne the mark ever since, as you see,” said Steerforth; “and she’ll bear it to her grave, if she ever rests in one—though I can hardly believe she will ever rest anywhere….”

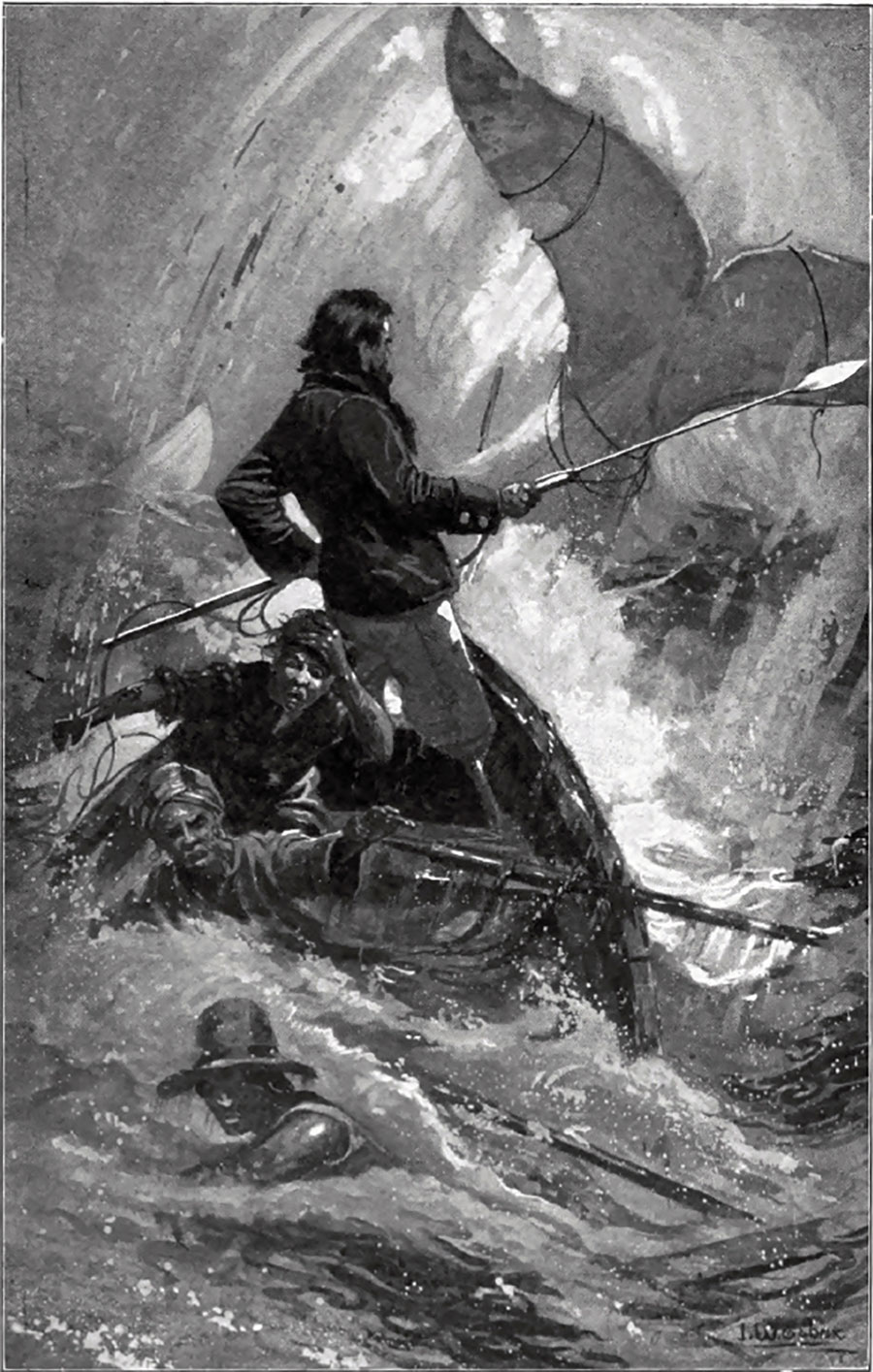

Captain Ahab

Threading its way out from among his grey hairs, and continuing right down one side of his tawny scorched face and neck, till it disappeared in his clothing, you saw a slender rod-like mark, lividly whitish. It resembled that perpendicular seam sometimes made in the straight, lofty trunk of a great tree, when the upper lightning tearingly darts down it, and without wrenching a single twig, peels and grooves out the bark from top to bottom, ere running off into the soil, leaving the tree still greenly alive, but branded. Whether that mark was born with him, or whether it was the scar left by some desperate wound, no one could certainly say.

• • •

So powerfully did the whole grim aspect of Ahab affect me, and the livid brand which streaked it, that for the first few moments I hardly noted that not a little of this overbearing grimness was owing to the barbaric white leg upon which he partly stood. It had previously come to me that this ivory leg had at sea been fashioned from the polished bone of the sperm whale’s jaw.

— Moby Dick, Chapter XXVIII

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

In other novels, such as Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, not only does the character’s disfigurement brand him with distinctive physical and symbolic attributes, but the cause of that disfigurement actually initiates and propels the plot forward to its conclusion.

Clearly Captain Ahab’s prosthetic leg is not simply the sign of an encounter gone wrong with the great white whale; more meaningfully, it serves as an emblem of the doomed obsession that will lead a vengeful Ahab to pursue his quarry to the point of his own death and that of his entire crew. At the same time, the mysteriously acquired facial scar intimates that this “grand, ungodly, god-like man” is a tragic hero in the classical sense: someone blessed from birth who was destined for potentially great things; yet was also cursed with hamartia: the inherent flaw that will inevitably bring about his downfall.

Erik “The Phantom”

One of five watercolors illustrating the first American edition of Phantom of the Opera (André Castaigne, 1911)

Was all this serious? The truth is that the idea of the skeleton came from the description of the ghost given by Joseph Buquet, the chief scene-shifter, who had really seen the ghost. He had run up against the ghost on the little staircase, by the footlights, which leads to “the cellars.” He had seen him for a second—for the ghost had fled—and to anyone who cared to listen to him he said:

“He is extraordinarily thin and his dress-coat hangs on a skeleton frame. His eyes are so deep that you can hardly see the fixed pupils. You just see two big black holes, as in a dead man’s skull. His skin, which is stretched across his bones like a drumhead, is not white, but a nasty yellow. His nose is so little worth talking about that you can’t see it side-face; and the absence of that nose is a horrible thing to look at. All the hair he has is three or four long dark locks on his forehead and behind his ears.”

— The Phantom of the Opera, Chapter I

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Best known to audiences by way of actor Lon Chaney, Sr.’s superb characterization in the 1925 silent film adaptation and, much later, the Andrew Lloyd Webber hit Broadway musical, the figure of the mysterious “ghost” who haunts the Paris Opera House is an invention of French author Gaston Leroux. His 1910 novel centers around the warped devotion of Erik—a freakishly disfigured recluse—for the up-and-coming soprano Christine Daaé. Unlike the tragic hero Ahab, Eric is cast in the novel as a murderous, monstrous villain; and yet we cannot help but feel some sympathy for his plight. As Christine discovers (while held captive by him), Eric is also a musical genius of extraordinary emotional depth. Having heard the Phantom perform his masterpiece, Don Juan Triumphant, she describes it as “one long, awful, magnificent sob. But, little by little, it expressed every emotion, every suffering of which mankind is capable. It intoxicated me….”

In other words, he is the very epitome of what literary critics call an “anti-hero.”

Only in the novel’s epilogue do we learn of Erik’s origins and his true nature. He was born that way! A pathetic victim of the ultimate “birthmark,” Eric from a young age was forced to wear a mask to hide his ugliness, which was “a subject of horror and terror to his parents.” Yet he was also gifted with prodigious mental and physical prowess. Cast out of society throughout his life because of his hideous appearance, his soul itself learned to become ugly out of self-defense. And yet, “with an ordinary face, he would have been one of the most distinguished of mankind! He had a heart that could have held the empire of the world; and, in the end, he had to content himself with a cellar. Ah, yes, we must needs pity the Opera ghost.”

If anything is to be learned from this compelling tale, it is this: trust not in mere appearances.

Santiago

The old man was thin and gaunt with deep wrinkles in the back of his neck. The brown blotches of the benevolent skin cancer the sun brings from its reflection on the tropic sea were on his cheeks. The blotches ran well down the sides of his face and his hands had the deep-creased scars from handling heavy fish on the cords. But none of these scars were fresh. They were as old as erosions in a fishless desert.

Everything about him was old except his eyes and they were the same color as the sea and were cheerful and undefeated.

— The Old Man and the Sea

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Ernest Hemingway’s novels and stories are rife with characters whose wounds and scars betoken a vast range of behaviors and meanings. Depending on the circumstances, these scars may imply lasting damage to the characters’ psyche; or hint at their qualities of courage and self-control in the face of impossible odds and certain defeat.

Nowhere is this truer than in his award-winning 1952 novel, The Old Man and the Sea, where Santiago’s scars—described on the very first page of the book—foreshadow his later demonstration of mental discipline and sheer physical endurance as the wounds of his hands open once more during the epic battle against the giant marlin; and even as the sharks subsequently devour his hard-won catch.

Back on shore, scarred still and now bleeding again, he remains undefeated: not crushed by self-pity, but asleep in his shack, “dreaming about the lions.”

On the Internet one often runs across this inspirational quote from Rumi, the 13th-century Persian poem and Sufi mystic:

The wound is the place where the Light enters you.

While that may be true, here in the non-fiction world of flesh-and-blood humans the resulting scar is just that: a visible reminder of physical trauma. By all means, let the light enter you. As for the scar, there is no reason not to try and banish it from view with silicone sheeting, derma rollers, or any of the other effective scar-reduction solutions offered by Rejuveness!